Traditional Japanese tattooing traces its origins to the art form of ukiyo-e, literally translated as ‘pictures of the floating world’. Ukiyo-e, a genre of picture making, evolved in the seventeenth century in Japan’s theatre and brothel districts, but soon incorporated illustrations of a wide range of literature and subject matter. Thanks to the generosity of local collectors Canterbury Museum holds about 500 uyiko-e artworks in the collection, with a handful on display in the Asian Arts Gallery.

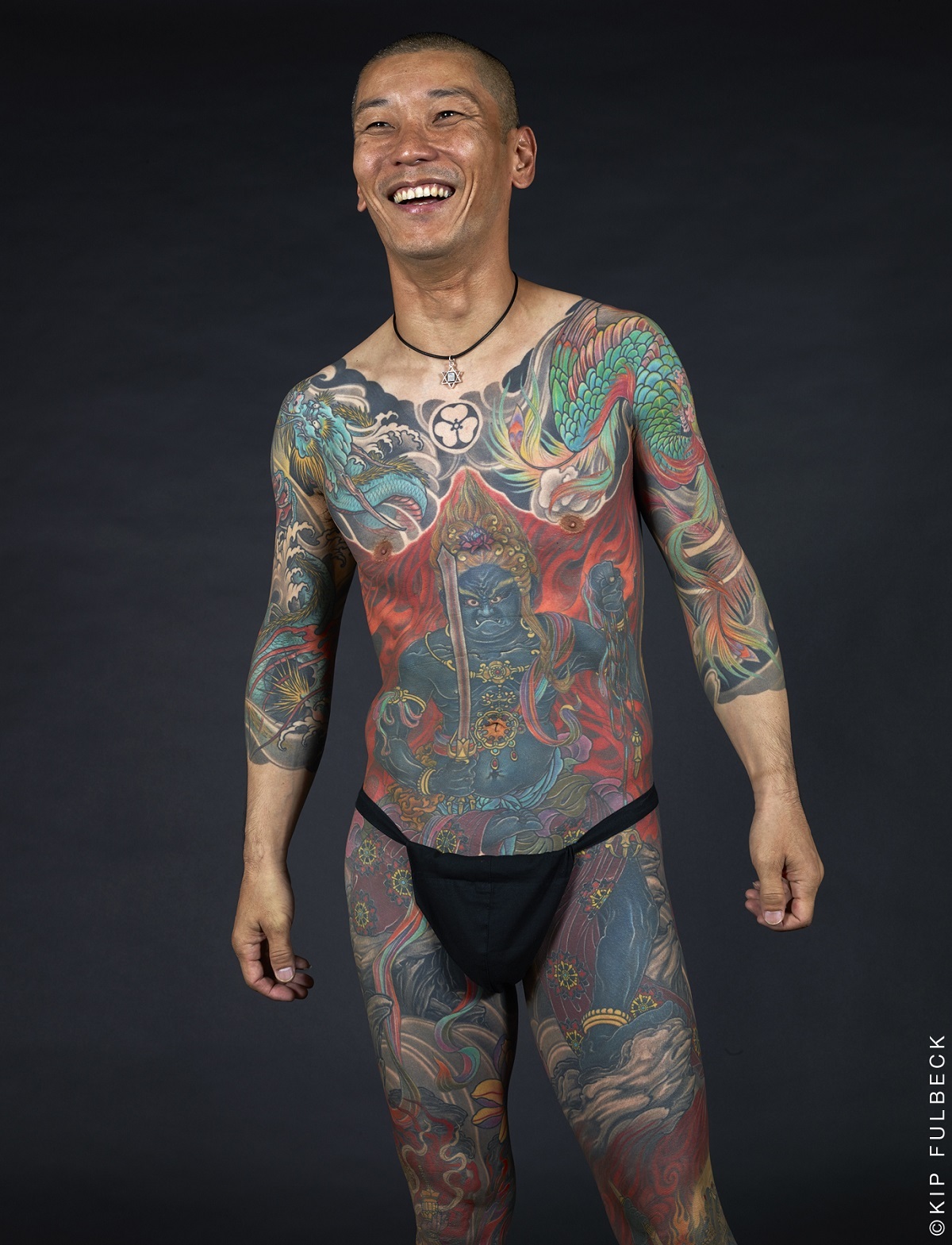

Canterbury Museum Research Fellow, Dr Richard Bullen, tells the story behind the tattoos in our special exhibition ‘Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in a Modern World’.

We often think of the artist who designed an ukiyo-e print in the Edo period (1603-1867) as solely responsible for the end product, but the manufacture of wood-block printing in Japan’s last feudal period – named after the seat of political power, Edo (today Tokyo) – was really a co-operative affair.

A publisher was at the heart of the process, commissioning others to carry out the various steps, of course in the expectation of profiting from the investment. A key person in this exercise was the block cutter, whose finished carved blocks were sent to the printer, who produced large numbers of the finished print products.

In the nineteenth century, many of these block cutters were identified by name on the prints, a signal that their art was recognised as a respected part of the printmaking process. Some acclaimed ukiyo-e artists, such as Hokusai, actually apprenticed as block cutters. And it was this class of artisan that oversaw the nineteenth century boom in the art of irezumi (tattooing). The term for block cutter – horishi – was even adopted by the tattooists. Irezumi was born out of the world of ukiyo-e.

It is not surprising, therefore, as the Perseverance exhibition amply demonstrates, that many pictorial and design conventions of nineteenth century ukiyo-e are so strongly evident in Japanese tattooing. One artist in particular stands out as exerting great influence over the tattooists’ art, Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861).

Kuniyoshi, an intemperate man, was drawn to the bizarre, fantastic and extreme. Amongst his greatest achievements were the inventive picturing of mythical creatures – giant carp, snakes and other animals, dragons, sea creatures and ghosts of all kinds, and their battles with humans. His designs fill pictorial spaces to bursting point with fine draftsmanship and a taste for the extraordinary and fantastic – the restraints of the printed format could hardly contain his energy.

Canterbury Museum has a long history of collecting and exhibiting the arts of East Asia, including ukiyo-e. In 1958 the Museum opened the first permanent space in Australasia dedicated to East Asian art. Today many of the objects in the Museum’s permanent collection are on display in the Hall of Asian Decorative Arts on Level 3, including some fine ukiyo-e prints and paintings. This includes a painting by one of the founders of the genre, Hishikawa Moronobu (1618–1694).

Moronobu’s family business was fabric decoration and embroidery, and he remained productive in fabric design even after he became a successful ukiyo-e artist. The painting evidences this specialist interest in the sartorial. The pattern of the figure’s kosode (a kimono with a small wrist opening) in light blue and red is a form of yūzen dying which was also popular in the nineteenth century. It is produced by twisting and tying small pinches of fabric prior to dying which, when untied, leave white (undyed) rings.

One of the prints on display is a scene from a kabuki play, showing a geisha – sword in hand – at the moment she is about to sever one of her own fingers. She holds a wad of paper in her mouth, to clench as she undertakes the act. She is carrying out the self-amputation to demonstrate her commitment to the man who is helping her refuse the advances of an unwanted suitor. Marking the body (including tattooing) was a common way to mark one’s devotion to another in Edo period culture.

Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in a Modern World at Canterbury Museum until 13 August 2017.