Canterbury Museum’s current exhibition He Uru Hou: Our Native Plants explores both Māori and European encounters with the native plants of Aotearoa New Zealand. This blog outlines some of the archaeological evidence that tells us how Māori in Canterbury cultivated plants for food.

Southern Māori deliberately cultivated several native plant species for food and textiles and archaeology can help identify where and how these species were used.

Two of the most important plants to Māori in Canterbury were tī kōuka (cabbage tree, Cordyline australis) and karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus). South Canterbury contains many examples of historic umu tī (earth ovens) that were used to cook the stem and tap root of tī kōuka. These roots were harvested between late spring and autumn, when carbohydrate levels were highest.

Umu tī are usually round pits with raised rims between 2 and 4 metres across. Stones were heated to high temperatures in the base of the umu and water was poured on the stones to make steam. Baskets containing the kāuru (prepared stems of the tī kōuka) were placed in the umu and then covered with leaves and soil. It could take up to two days to steam the kāuru in the umu tī. It was then dried and stored until needed. Kāuru was probably the most important plant food for southern Māori and para kāuru (cabbage tree groves) were planted throughout Canterbury.

Karaka was also a valuable food source, although the seeds contain a toxin and must be soaked and steamed to make them safe to eat. Canterbury is well outside of the natural range of karaka but deliberately-planted stands of this special tree are found near historic settlement sites on Horomaka (Banks Peninsula) and the Kaikōura coast. These stands of trees are sometimes the only visible evidence that people once lived in particular places.

Aruhe, the rhizome of bracken fern (Pteridium esculentum), was another important plant food. Harvested from forest margins and areas of open ground (often deliberately cleared to encourage the growth of bracken ferns), the rhizomes were dried for storage and then soaked in water before being roasted. The cooked aruhe was beaten with a patu aruhe (pounder) on a stone anvil to soften it and make it easier to remove the stringy fibres. Canterbury Museum looks after examples of rare wooden patu aruhe found in the region.

Māori also used several introduced species of plants. The East Polynesian colonists who settled Aotearoa New Zealand brought with them at least six species: kūmara (sweet potato, Ipomoea batatas), taro (Colocasia esculenta), uwhi (yam, Dioscorea spp,), hue (gourd, Lagenaria siceraria), tī pore (Cordyline fruticosa) and aute (paper mulberry, Broussonetia papyrifera). Most of these tropical species could only grow in the far north of the country, but kūmara was cultivated as far south as Horomaka (Banks Peninsula).

Kūmara was probably the most important of the early introduced food crops. It is sensitive to the cold and frost tender, and would have been difficult to grow in large quantities in Canterbury. Several different varieties were cultivated using methods such as planting on stone mounds or in rows on gently sloping ground. Sand and gravel were often added to improve drainage and to make the soil warmer. After harvesting, kūmara were stored in kete (flax baskets) in storehouses either below ground or in above ground structures such as pataka or whata.

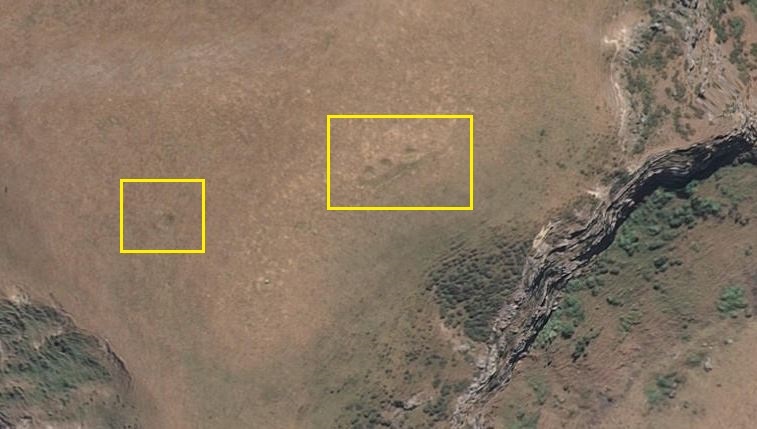

The southernmost evidence of kūmara gardening is found at Taumutu and Birdlings Flat on the shores of Waihora (Lake Ellesmere), where large borrow pits have been recorded. These borrow pits are where gravel was extracted to modify garden soils to improve growing conditions. Similar borrow pits have been recorded near Woodend and Tūahiwi.

Other archaeological evidence of kūmara gardening includes stone rows at Panau, near the entrance to Little Akaloa Bay, Stony Bay, Goughs Bay and Paua Bay.

Microscopic plant remains can provide information about plant use. Phytoliths are silica casts of plant cells that form in the leaves and stems of many species. When the plant dies and decays phytoliths are left behind in the topsoil. Studying such phytoliths can tell us which plants grew in an area in the past.

To date there has been little analysis of phytoliths from Canterbury archaeological sites, but they have been identified on a northwest facing slope overlooking Waihora in soil that has had gravel added to it. This particular site also has rectangular raised rim pits on the ridgeline that are probably the remains of kūmara storage pits. They were likely covered with a thatched roof supported by a central row of posts. Kūmara storage pits like these are rare in Canterbury and unfortunately this site has not yet been dated.

There is still much to learn about pre-European horticultural practices in Canterbury. Garden features and kūmara storage pits have been radiocarbon dated to the fourteenth century in other parts of the country. Some of the Canterbury sites are likely to be equally early, but there are indications that by the end of the sixteenth century these gardens may have been abandoned either because of social upheaval, climate change or a combination of the two. This period coincides with a climatic phase known as the Little Ice Age, which was colder, wetter and windier than today and would have made the growing of kūmara in what was already a marginal zone more difficult. There has also been little archaeological research into plant cultivation and use both immediately prior to and following European contact.

Learn more about traditional Māori uses for the native plants of Aotearoa New Zealand in He Uru Hou: Our Native Plants. On until 9 February.