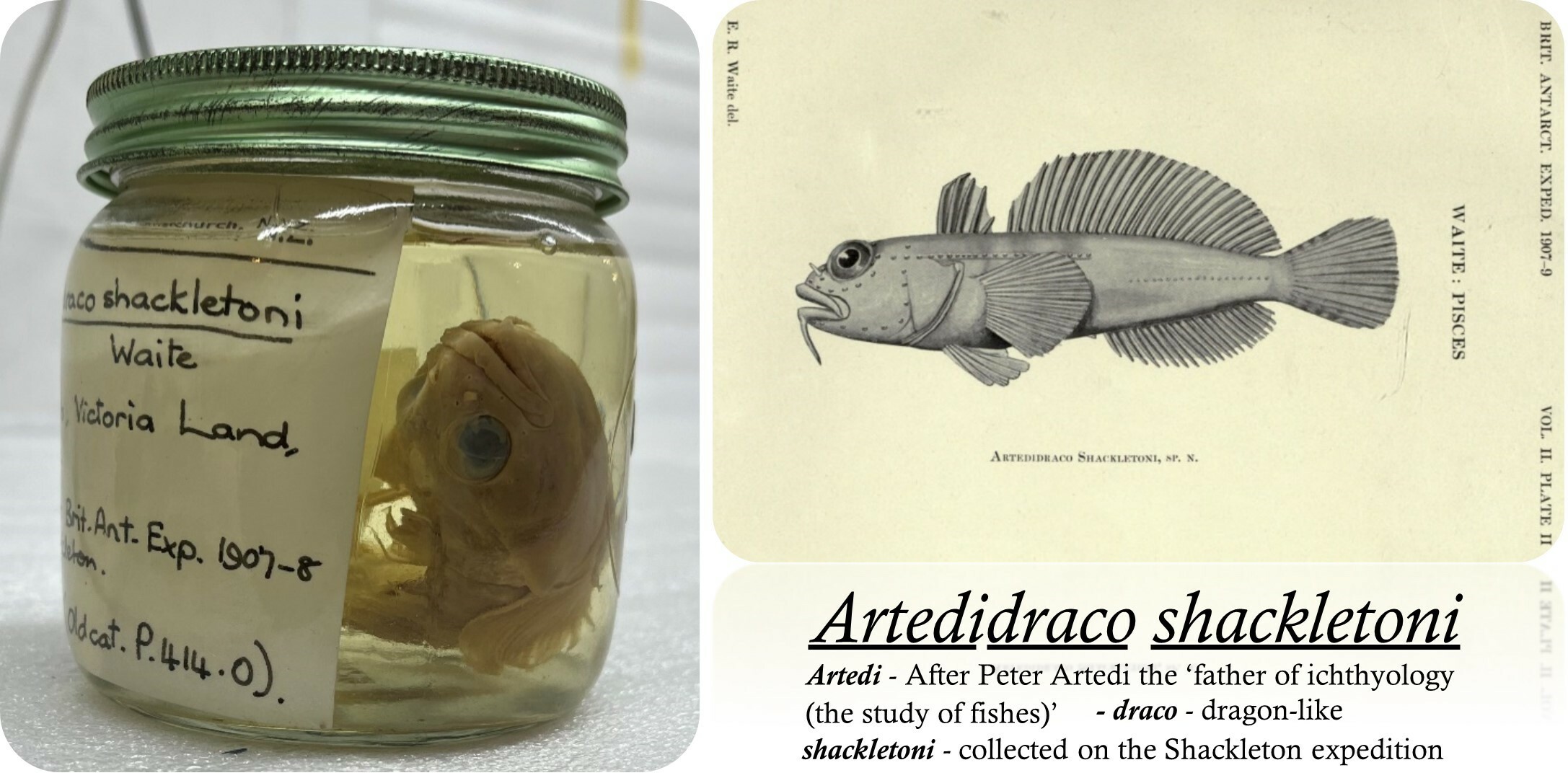

If you head into the Museum's wet collection store, which contains the natural history specimens preserved in liquids like ethanol and formalin, you will find a special fish named Artedidraco shackletoni.

This fish tells us an interesting story about the intersection of Ernest Shackleton’s Antarctic expedition, Canterbury Museum Director and fish researcher Edgar Ravenswood Waite, and the Museum’s natural history collection.

This is the holotype specimen, meaning that this exact fish was used to describe the new species. It is is of special importance because it is the physical voucher and "name bearer", meaning that if there were uncertainties about whether another fish specimen belonged to Artedidraco shackletoni, this is the specimen it would be compared to.

Artedidraco shackletoni is from a group known as barbelled plunderfishes, which dwell on the bottom of the ocean where they sit and wait for their prey such as crustaceans to cross their path.

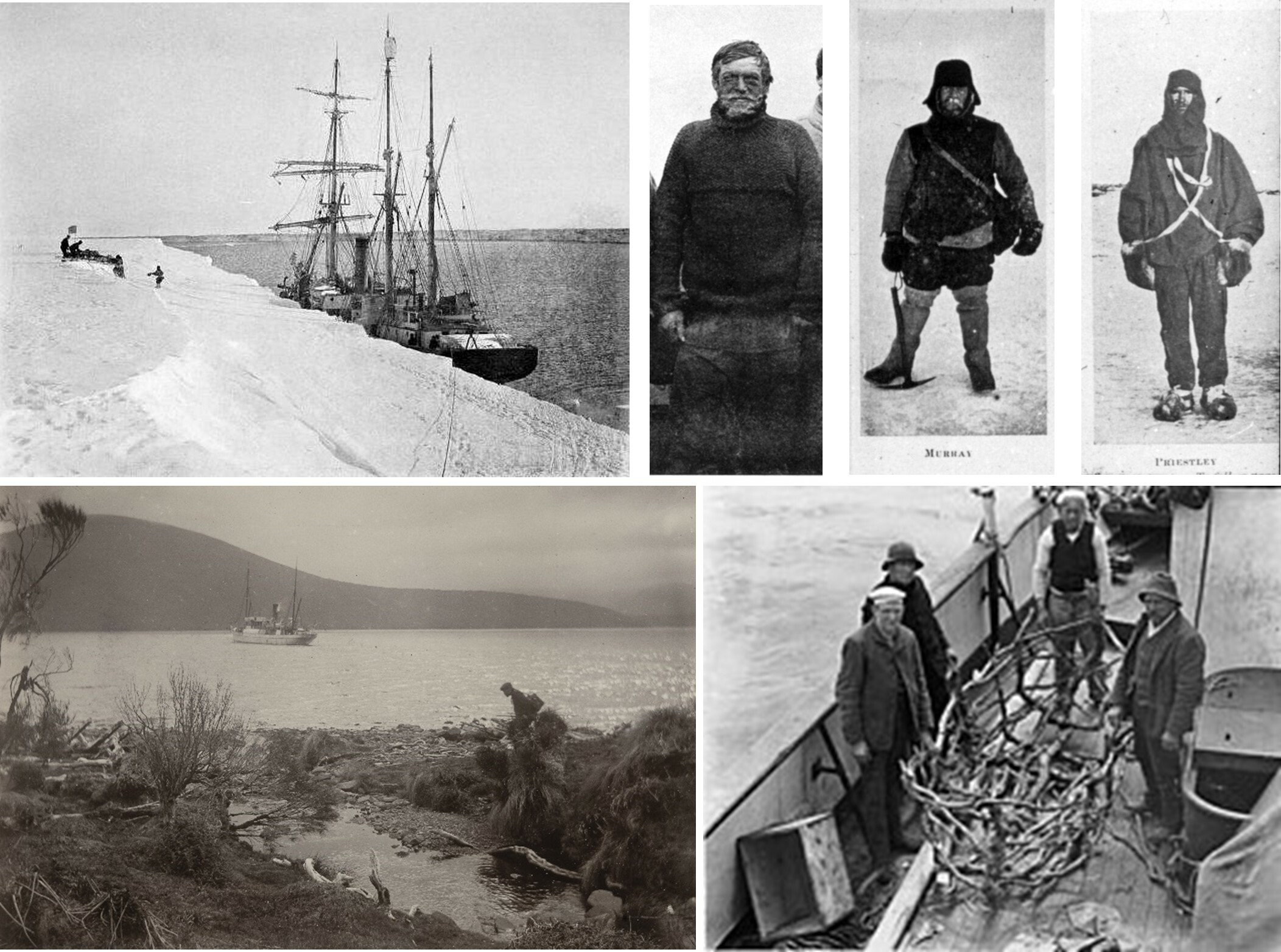

The story of this particular fish coming to Canterbury Museum starts at Cape Royds, Antarctica, in 1908. Shackleton’s 1907–1909 expedition on the Nimrod is most well-known for the unsuccessful attempt to reach the South Pole, the first successful ascent of Mount Erebus and the first successful attempt to reach the South Magnetic Pole. Less well-known is the extraordinary time and energy spent collecting biological specimens, including everything from tiny plankton just millimetres in size to enormous starfish – the largest recorded at 9 inches long. Collecting marine life in Antarctica was particularly challenging as holes had to be dug into the sea ice before either dredges or baited traps could be dropped down into the ocean.

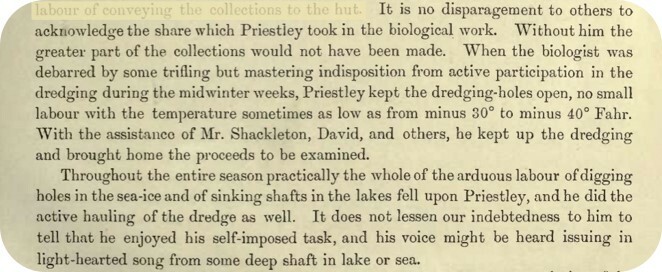

On the expedition was Raymond Priestley, 21, who was studying to become a geologist. He undertook much of the biological sampling work and his exceptional efforts are mentioned on several occasions by James Murray, the expedition biologist, in his paper 'On collecting at Cape Royds', including the excerpt below.

With his constant work battling the sea ice, it is most likely that Priestley collected the first ever specimen of Artedidraco shackletoni.

While the Antarctic expedition was underway, Waite was working as Curator of Canterbury Museum, a position he held from 1906 until 1914. Just prior to the Nimrod’s departure for Antarctica, Waite had returned from his own expedition to the sub-Antarctic aboard the Hinemoa in November 1907. As well as making many scientific observations, the Hinemoa also collected the surviving crew from the Dundonald which had been wrecked on Disappointment Island in March 1907.

Like the Antarctic expedition, the trip to the sub-Antarctic was undertaken for scientific discovery. However, Waite’s records from the trip imply that he had more success in collecting and observing birds than his usual fish on this trip. On arrival at Disappointment Island he writes, “I went ashore with the others and we were first greeted by a mob of penguins … which came hopping down the rocks”.

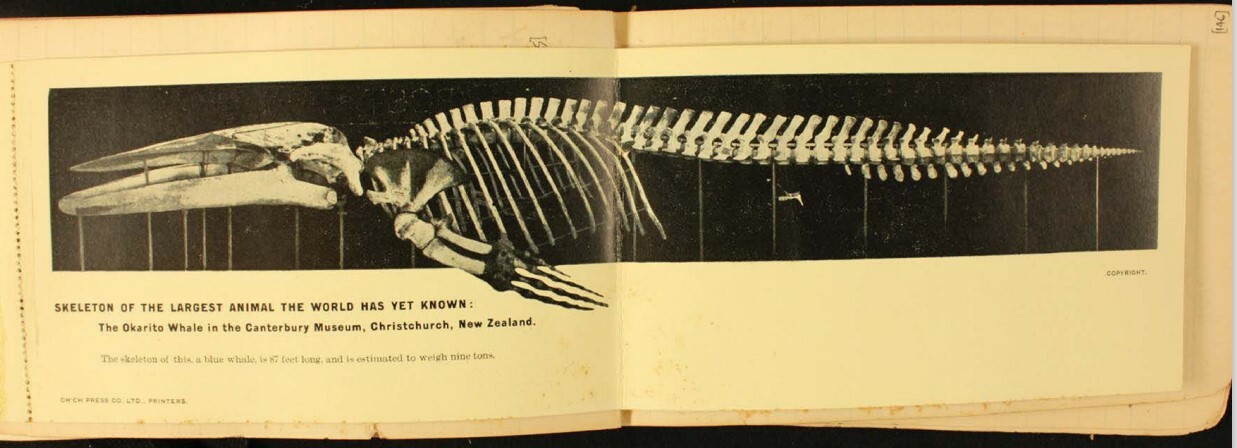

Aside from the observations and samples from the Hinemoa trip, Waite was kept occupied for several years while the Nimrod expedition was ongoing by the infamous Ōkārito blue whale, which arrived at the Museum in 1908 and which Waite described on first sighting as a "truly colossal brute".

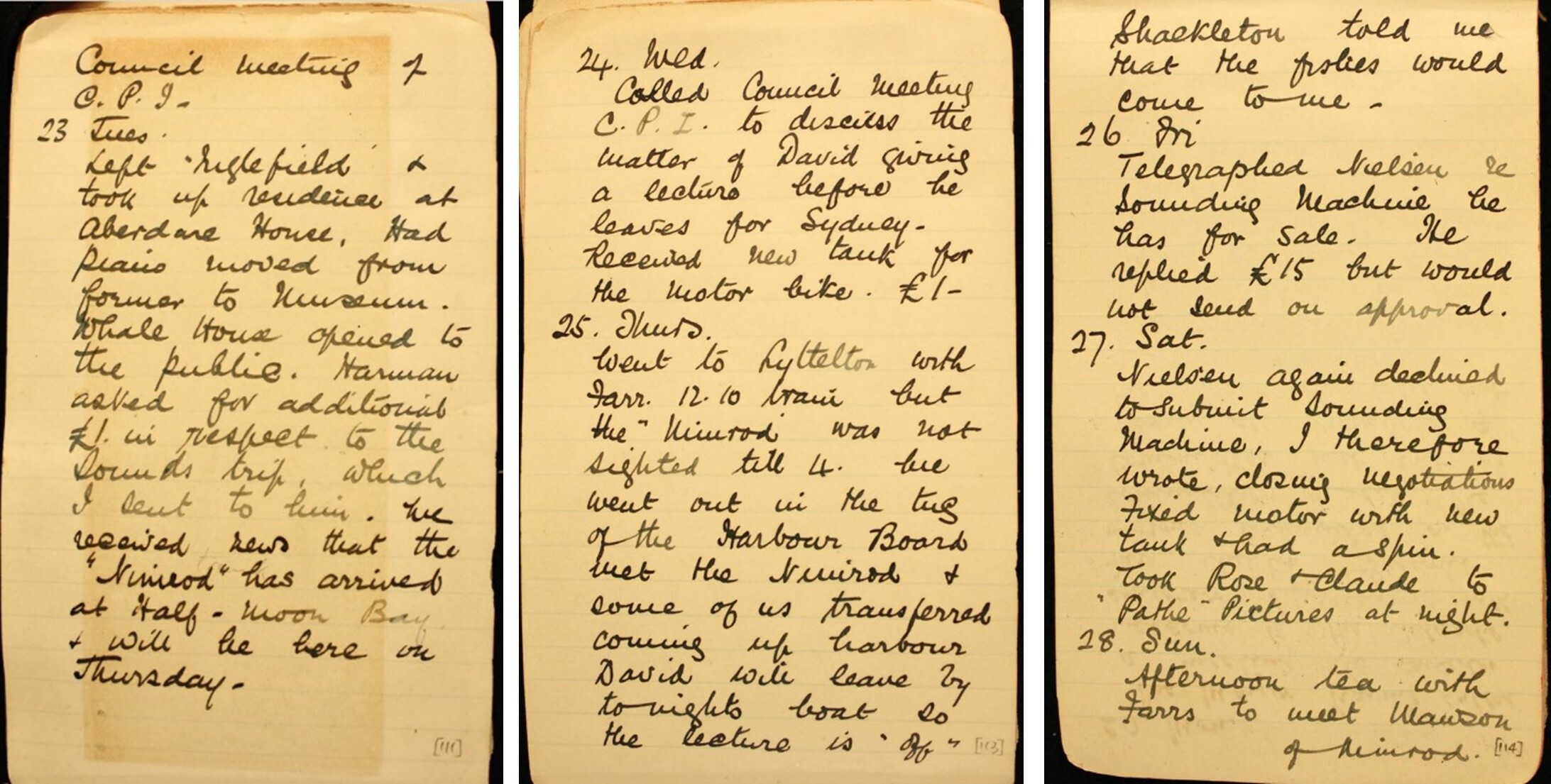

Finally, on 23 March 1909, having grappled with the logistics of including a blue whale in the Museum’s collection for the last year, Waite writes that, “We received news that the Nimrod has arrived at Half-moon Bay and will be here on Thursday,” followed by an entry on 25 March, “Went to Lyttelton with Farr. 12:10 train but the Nimrod was not sighted till 4. We went out in the tug of the Harbour Board met the Nimrod and some of us transferred coming up harbour…. Shackleton told me that the fishes would come to me.”

Coincidentally, Shackleton’s arrival back from the expedition was the date that Canterbury Museum’s blue whale was first able to be viewed by the public. In the diary entry (above) from 23 March, Waite notes “Whale house opened to the public”.

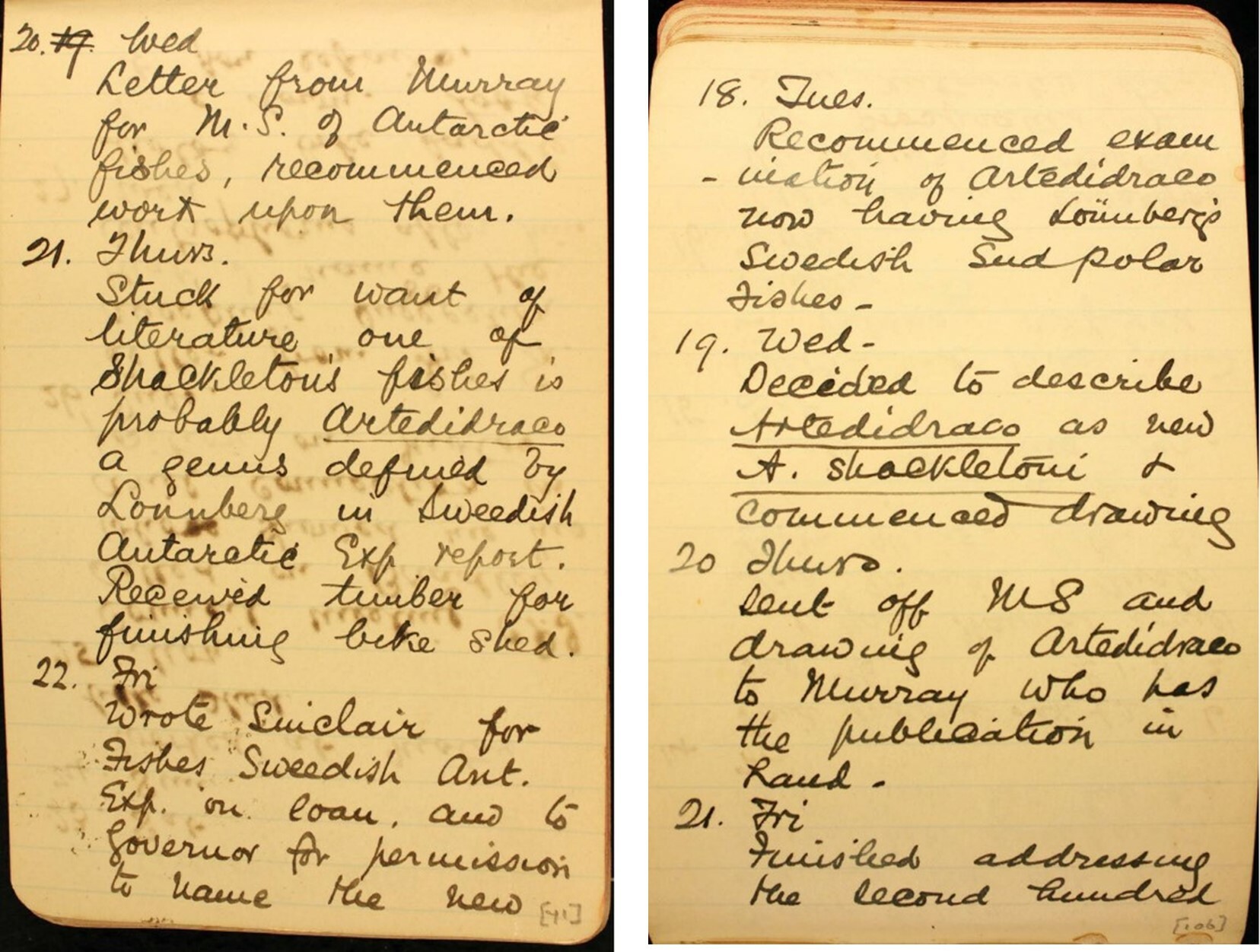

On receiving the Antarctic fishes however, Waite did not immediately work on the specimens, instead spending most of 1909 in Australia, returning to the Museum in August. Shortly afterwards he was prompted to look at the Antarctic fishes. Waite’s diary entry on 20 October 1909 reads, “Letter from Murray for M. S. of Antarctic fishes, recommended work upon them”. This evidently prompted immediate action from Waite with an entry the next day of, “Stuck for want of literature, one of Shackleton’s fishes is probably Artedidraco a genus defined by Lonnberg in Swedish Antarctic Exp. Report”. By 27 October the following week, Waite had identified all of the Antarctic fishes, except one which he assumed to be Artedidraco. In January 1910 the necessary literature arrived in the post, and Waite confirmed it as Artedidraco as he suspected. However, as it did not match any of the known species of this group he gave it, and its species, the new name Artedidraco shackletoni.

Some of the more notable descriptions of this fish in the species description written by Waite include: “The whole fish is scaleless, but covered with mucus” and “almost colourless”. All useful and important information to note when you have come across a new species found in a land still being explored.