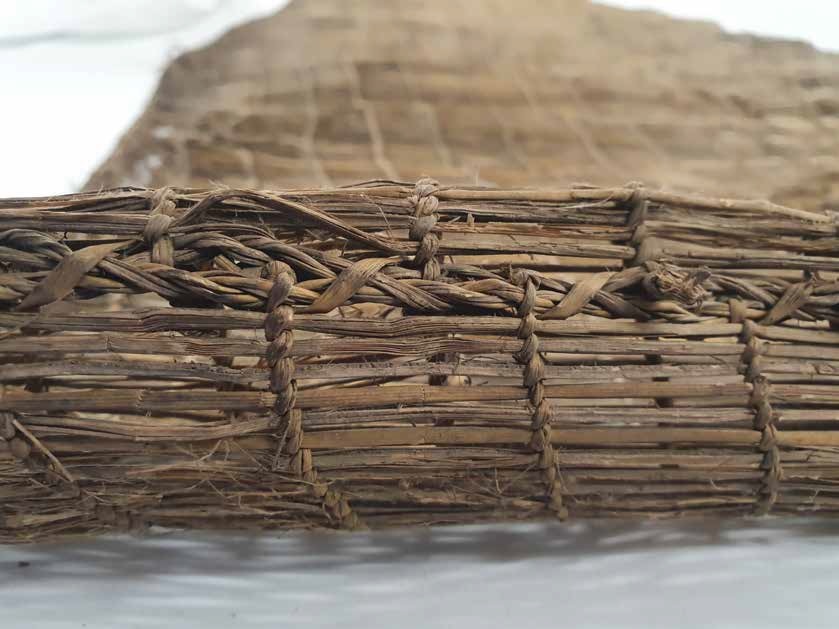

Canterbury Museum cares for two extremely rare and fragile Māori kupenga (nets) designed to catch īnaka or whitebait.

These kupenga, carefully woven from harakeke (flax), are almost identical in design to the scoop nets used by modern whitebaiters.

The nets are part of the small amount of physical evidence we have documenting how Māori in Te Wai Pounamu (the South Island) caught ikawai (freshwater fish).

Because most Māori fishing equipment was made from biodegradable material, little of it has survived into the modern day.

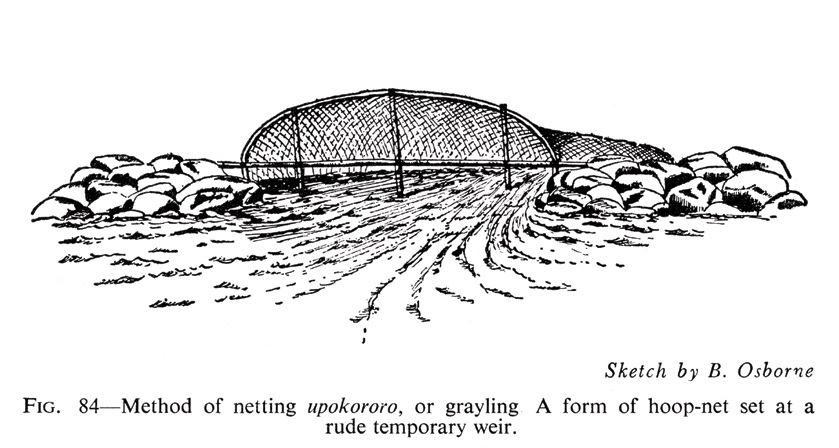

A new paper by Emeritus Curator Roger Fyfe and Senior Curator Human History Julia Bradshaw, published in Records of the Canterbury Museum, examines the extensive range of techniques Māori in Te Wai Pounamu used to catch, prepare and consume eight species of ikawai: five species of galaxiid, the extinct upokororo (grayling) and two types of paraki (smelt), which are also known as cucumber fish.

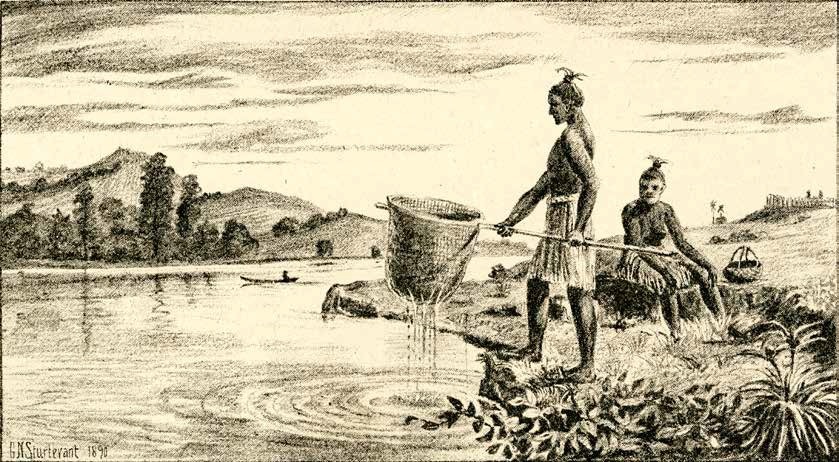

Early European descriptions of Māori freshwater fishing practices indicate Māori were well aware of ikawai life cycles and set their nets when they knew the fish would be migrating to or from the sea.

Māori in Te Wai Pounamu used a variety of net designs depending on which species they were targeting.

Large quantities of juvenile fish, known as īnaka or mata were harvested between August and January as they swam upstream after hatching in the sea. A second harvest, targeting sea-bound migrating adult fish, took place in autumn.

Īnaka were typically caught using scoop nets like the two in the Museum’s collection. Pirita (supplejack) was bent into hoops to form the waho (mouths) of the nets.

The long handles of the scoop nets could be detached to allow them to be used as set nets.

Adult fish, particularly in larger rivers, lakes and estuaries, were often caught in seine nets that were weighed down with stones and dragged through the water.

These nets could be very large. William Phillipps, writing in 1926, described nets being made at Waihora (Lake Ellesmere) to catch paraki that were 1.8 metres tall at the mouth and 27 to 91 metres long. Gaps in the weave of the nets seldom exceeded 1.5 mm, Phillipps wrote.

Unfortunately none of these large seine nets have survived into the present day.

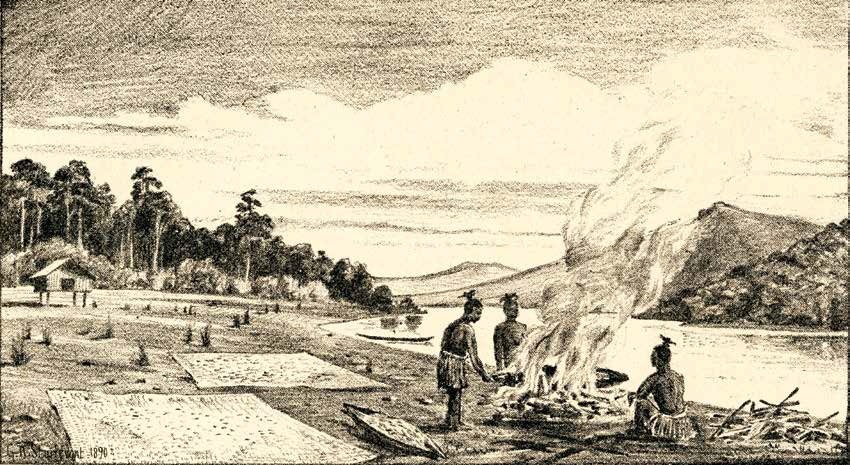

Īnaka were typically eaten boiled or steamed in an umu (earth oven). They could also be dried and then eaten during lean winter months, sometimes beaten into mashed aruhe (fern root).

Paraki were probably cooked, preserved and stored in a similar way.

The last known upokororo specimen was caught in the late 1920s or early 1930s. One European account describes these fish being cooked on a rara (grid) inside a hāngi (earth oven).

The kupenga in Canterbury Museum’s collection are a fragile reminder of a crucial economic activity in pre-European Te Wai Pounamu.

Click here to read Roger and Julia's full article in Records of the Canterbury Museum.