Being unhappy with how you look in photos is the bane of the digital age. But our ancestors were smoothing wrinkles and hiding double chins long before filters and Photoshop.

While digitising and cataloguing over 75,000 portraits of Cantabrians from the early 1900s, Canterbury Museum’s inventory team were surprised to learn just how heavily people’s faces could be edited. Wrinkles were erased, freckles removed and archbishops made to look 20 years younger. And there were plenty more unusual and surprising things waiting to be discovered.

The Clifford Collection of photographs is now digitised, online and fully searchable. Have a look and see if you can find a portrait of a relative.

Henry Herbert Clifford (1872–1949) was the son of the Dunedin photographer Robert Clifford. He began his photography career in Christchurch as an operator for Standish and Preece before striking out alone as a competitor, opening a studio of his own in 1902. In 1980, his son Ogilvie Clifford donated an archive of over 77,000 glass plate and film negatives to Canterbury Museum.

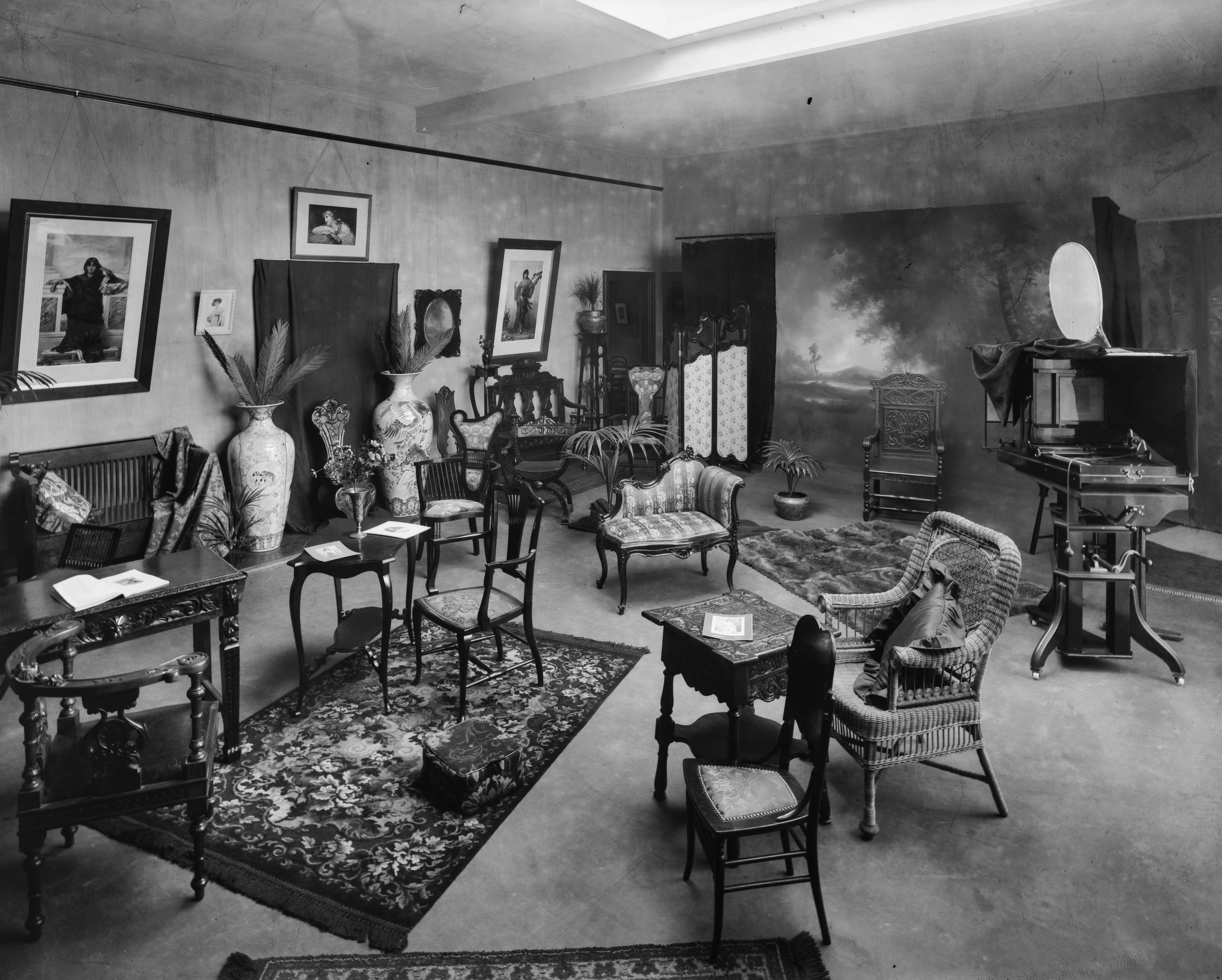

Clifford marketed himself not just as a simple photographer, but as an artist. He ran frequent advertisements in the papers promoting his “unerring artistic instinct”. This creative approach meant some portraits were elaborately staged. Clifford’s studio was full of furniture, props, ornaments and painted backdrops. Mock gardens and beach scenes could be conjured in his studio, complete with scattered leaves and footprints in the sand.

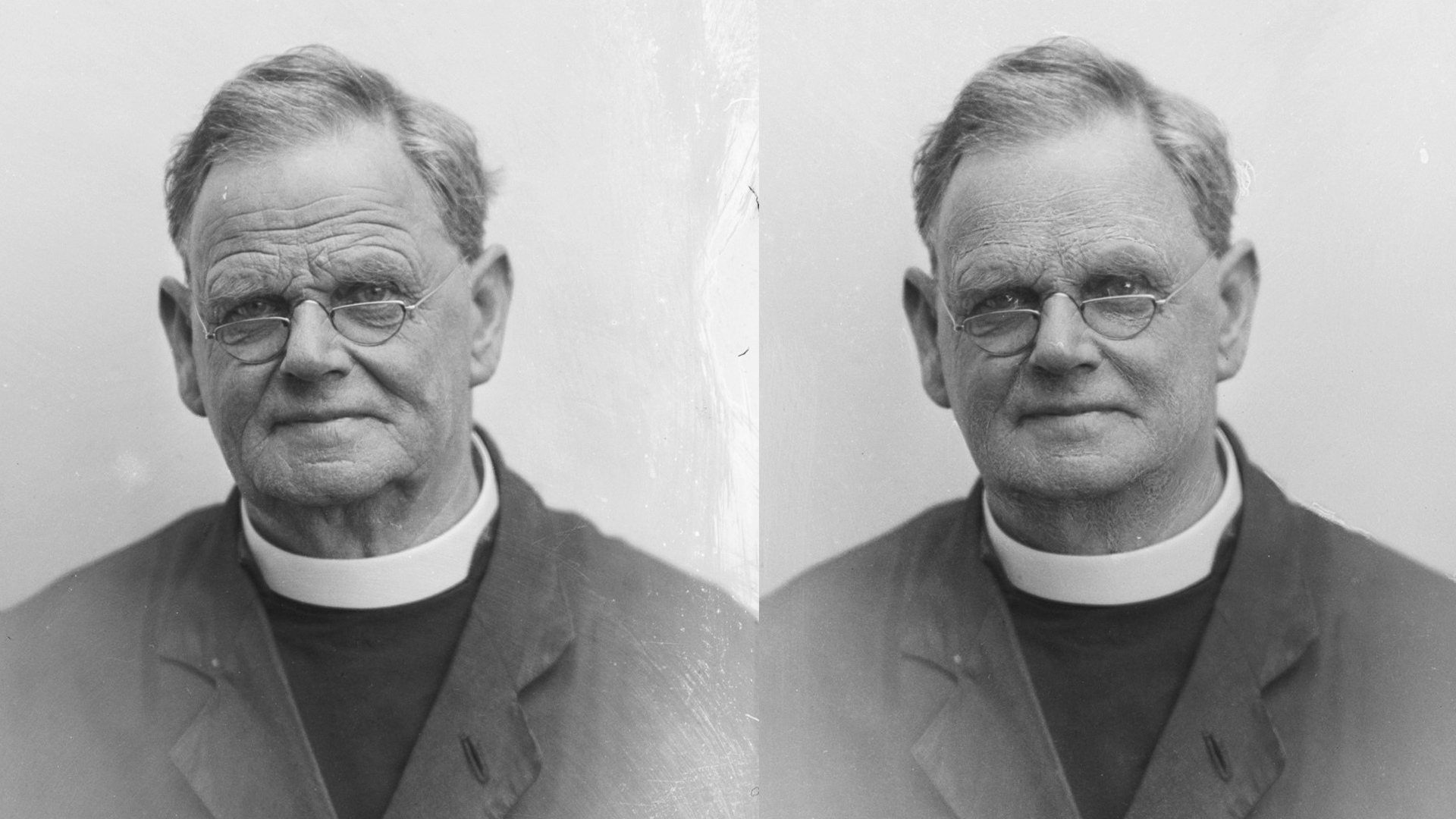

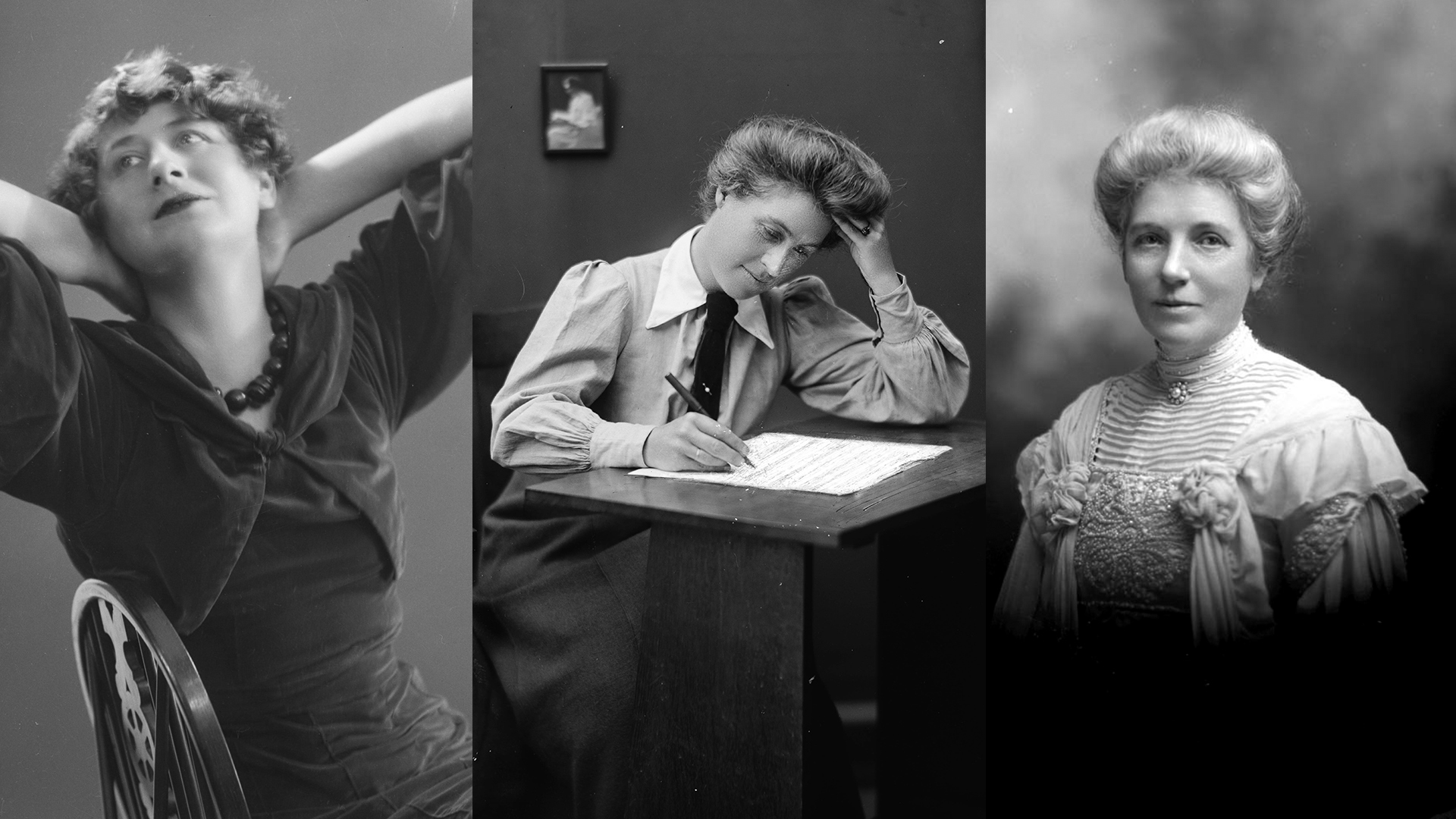

His creative spirit was also used to help customers look their best. Some of the glass plates in the Clifford Collection have two near-identical portraits exposed side-by-side. In some cases, one of the portraits has gone through the retouching process, while the other has been left unedited. The results are striking. Mr H Drummond had his freckles completely erased, while Churchill Julius, the first Archbishop of New Zealand, had his wrinkles almost completely smoothed out. Many women had the shadows, folds and creases removed from their faces and necks to the point that it is difficult to guess their ages. Even wisps of stray hair could be removed.

Most New Zealanders will be familiar with Clifford’s work from a rather prominent portrait of Kate Sheppard that found its way onto the $10 note, but there are plenty more famous faces to spot. Ngaio Marsh, the famous crime writer, appears in a number of playful poses. Blanche Baughan, the travel writer, poet, and prison reformer, studies industriously at her desk. Some unexpected celebrities also make appearances, like Ethelda Bleibtrey – a record-setting American swimmer, an Olympic gold medallist and the reason women no longer have to wear stockings in the pool.

It was essential that this precious collection was digitally preserved. The majority of the photographs are glass plate negatives, which are fragile and deteriorate over time. Some of the glass plates are spiderwebbed with deteriorated emulsion, which completely erases names and faces.

The glass plates are housed in cool storage, currently at the Museum's temporary storage facility in Hornby. Here controlled temperatures and relative humidity levels slow their degradation. But it was important to preserve the collection before the most significant portraits faced a similar fate.

Each glass plate is backlit and photographed from above in a darkened room to stop reflections. The plates are photographed in high quality with more pixel resolution than a 4K television. Cataloguers then worked their way through the digital versions of these plates, verifying that each one had a unique identification number and had been accurately digitised. They also added short descriptions to each image along with any notes or names on the photo. It took 6 years to digitise the Museum's 238,000 photographic negatives and slides, which includes the Clifford Collection. The project was partially funded by the New Zealand Lotteries Grant Board.

All this work means the collection is now preserved for the future. It also means the community can search the collection on our website and post any information they have about the images. With only a surname and a first initial to go on, it is impossible to know how many interesting and important people may be hiding in the collection.

And there are still plenty of mysteries to solve. Why is Mr P H Beale so solemnly wearing a clown costume? Why is Miss L Moore dressed as a bat? And what’s the story behind the Christchurch Ladies Banjo Band?

Explore the archive and see what you can discover!

Putting the Clifford Collection online is part of a project to create a digital inventory of the Museum’s entire collection of 2.3 million objects. The Inventory Project began in 2017 and has so far added 545,000 objects to the Museum’s database. Many large collections have now been fully digitised, including the W A Kennedy Collection of around 22,000 lantern slides and the Sir Heaton Rhodes Collection of 7,800 stamps.

Thanks to the New Zealand Lottery Grants Board for their invaluable support, which has been instrumental in making the digitisation of our collection a reality.